White Stork (Ciconia ciconia)

CAR summary data

Habitat and noted behaviour

Sightings per Kilometre

Please note: The below charts indicate the sightings of individuals along routes where the species has occured, and NOT across all routes surveyed through the CAR project.

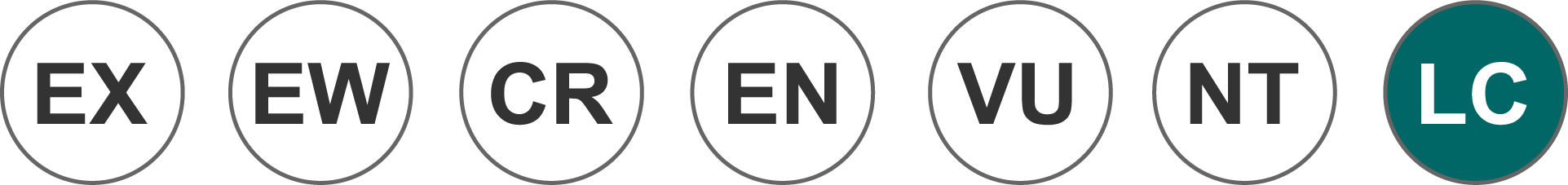

Regional Status

IUCN Data (Global)

IUCN 2024. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2024-1 (www)Assessment year: 2025

Assessment Citation

BirdLife International 2025. Ciconia ciconia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2025: e.T22697691A281839847. Accessed on 21 January 2026.Habitats:

Behaviour This species is a Palearctic migrant (del Hoyo et al. 1992) that travels with the assistance of thermal updrafts, the occurrence of which restricts the migratory routes the species can take (Hancock et al. 1992). For example the species must avoid long stretches of open water such as the Mediterranean Sea and must therefore bypass it on narrow fronts to the west or east (Snow and Perrins 1998, Van den Bossche 2002), after which it crosses the Sahara on a broad front (Brown et al. 1982). Once within Africa the species becomes considerably nomadic in response to changing abundances of food (e.g. locust swarms) (Hancock et al. 1992). It breeds from February to April in the Palearctic, whilst the tiny breeding population in South Africa breeds from September to November (del Hoyo et al. 1992). It nests in loose colonies of up to 30 pairs (Hancock et al. 1992, del Hoyo et al. 1992) or solitarily (del Hoyo et al. 1992). The main departure from the European breeding grounds occurs in August (Hancock et al. 1992) with the species travelling in large flocks (Brown et al. 1982, Hancock et al. 1992) of many thousands of individuals (Snow and Perrins 1998), generally arriving in Africa by early-October (Brown et al. 1982). It forages singly, in small groups of 10-50 individuals (Hockey et al. 2005), or in large flocks if prey is abundant and on its wintering grounds it may gather in large numbers (hundreds or thousands of individuals) at abundant food sources (e.g. locust swarms or grass fires) (Hancock et al. 1992). The species feeds diurnally (Hancock et al. 1992) and roosts communally at night in trees (Brown et al. 1982). Habitat The species inhabits open areas, generally avoiding regions with persistent cold, wet weather or large tracts of tall, dense vegetation such as reedbeds or forests (Hancock et al. 1992, del Hoyo et al. 1992, del Hoyo et al. 1992), shallow marshes, lakesides (Hancock et al. 1992, del Hoyo et al. 1992), lagoons (del Hoyo et al. 1992), flood-plains, rice-fields and arable land (Snow and Perrins 1998) especially where there are scattered trees for roosting (del Hoyo et al. 1992). Non-breeding During the winter the species shows a preference for drier habitats (Hancock et al. 1992) such as grasslands, steppe, savanna and cultivated fields (del Hoyo et al. 1992), often gathering near lakes, ponds (Hancock et al. 1992), pools, slow-flowing streams, ditches (del Hoyo et al. 1992) or rivers (Hancock et al. 1992). Diet The species is carnivorous and has a varied and opportunistic diet (del Hoyo et al. 1992). It takes small mammals (del Hoyo et al. 1992) (e.g. voles, water voles, mice, shrews, young rats (Hancock et al. 1992)), large insects (e.g. beetles, grasshoppers, crickets and locusts), adult and juvenile amphibians, snakes, lizards, earthworms, fish (del Hoyo et al. 1992), eggs and nestlings of ground-nesting birds, molluscs and crustaceans (Hancock et al. 1992). Breeding site The nest is constructed of sticks (del Hoyo et al. 1992) and is commonly positioned up to 30 m above the ground (Brown et al. 1982) in trees or on the roofs of buildings, as well as on pylons, telegraph poles, stacks of straw and other anthropogenic sites (including specially erected nesting structures), cliffs and occasionally among rushes on the ground (del Hoyo et al. 1992). The species nests solitarily or in loose colonies, often using traditional nesting sites (there are records of individual nests being used every year for 100 years) (Hancock et al. 1992, del Hoyo et al. 1992). Nesting sites are usually situated near foraging areas, but may be up to 2-3 km away (Snow and Perrins 1998). Management information Intensively grazed (> 1 cow per hectare) unfertilised grassland was found to attract a higher abundance of this species in Hungary (Baldi et al. 2005), and traditional livestock-farming practices such as creating herb-rich meadows for stock grazing and hay production are thought to be beneficial (Goriup and Schulz 1990). A model used to study the impact of different land use patterns on the species found that sequential (asynchronous) mowing of grasslands may increase the food supply for nestlings, thereby increasing reproductive success (as sequential mowing generates a small number of high-quality foraging patches throughout the breeding season) (Johst et al. 2001). A report by the International Council for Bird Preservation (ICBP) suggests that habitat management for the species should include the periodic flooding of meadows, the creation of a mosaic of native grasslands and meadows, and the retention or creation of ditches, ponds and lakes (Goriup and Schulz 1990). The report also advises management strategies in relation to electricity pylons (e.g. burying or marking aerial cables and preventing disturbance to nests during maintenance) to reduce the threats of electrocution and collision (Goriup and Schulz 1990). Due to the species's habit of defecating on its legs to regulate its body temperature in hot climates it is inadvisable to fit individuals with leg-rings for tracking purposes (dry uric acid builds-up on the legs and hardens around leg-rings, tightening them and leading to injuries) (Goriup and Schulz 1990). Other methods of monitoring movements such as satellite telemetry or patagial wing-tags are therefore advised (Goriup and Schulz 1990).Population:

In Europe, the total population size is estimated at 502,000-563,000 mature individuals, with 251,000-282,000 breeding pairs (BirdLife International 2021), and comprises the vast majority of the species' breeding population. Additionally there are at least 12,300 breeding pairs outside of Europe; roughly 11,000 breeding pairs in north Africa (data from the 2014 census for Morocco and Tunisia, and 2005 census for Algeria and Libya), 70 breeding pairs in Iraq, 4 breeding pairs in Israel, c. 1,250 breeding pairs in Central Asia (subspecies C. c. asiatica) (1,200 of which are in Uzbekistan) (Michael-Otto-Institut im NABU undated). A very small number were previously resident and breeding in South Africa, but it seems unlikely that this still exists (Rose 2025).Combining this breeding information gives a global population size of approximately 263,000-294,000 breeding pairs or 526,000-588,000 mature individuals.

Threats:

The species is threatened by habitat alteration including the drainage of wet meadows (Goriup and Schulz 1990, del Hoyo et al. 1992), prevention of floods on flood-plains (by dams, embankments, pumping stations and river canalisation schemes) (Goriup and Schulz 1990), conversion of foraging areas (del Hoyo et al. 1992), development, industrialisation and intensification of agriculture (Hancock et al. 1992) (e.g. mechanised ploughing of rough pastures to sow fertilised crops or swards of more productive grass varieties) (Goriup and Schulz 1990). It is also threatened by a shortage of nesting sites in some areas (del Hoyo et al. 1992) as, for example, the roofs of new rural buildings do not support nests and nest structures on pylons are frequently destroyed during maintenance work (Goriup and Schulz 1990). During the winter in Africa there may be high rates of mortality due to changes in feeding conditions owing to drought, desertification and the control of locust populations by insecticides (Goriup and Schulz 1990, Hancock et al. 1992). The species may also suffer as a result of the excessive use of pesticides (e.g. in Africa) (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hockey et al. 2005) and through eating poisoned baits put out to catch large carnivores (del Hoyo et al. 1992). Another serious threat is collision with and electrocution from overhead powerlines (del Hoyo et al. 1992), especially whilst on migration in Europe (Hancock et al. 1992). The species is hunted for food and sport (del Hoyo et al. 1992), mainly on migration (Hancock et al. 1992) and in its winter quarters (Goriup and Schulz 1990).Conservation measures:

Conservation Actions UnderwayThis species is listed on Annex I of the EU Birds Directive, Annex II of the Bern Convention and Annex II of the Convention on Migratory Species, under which it is covered by the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement (AEWA). The eastern and western European populations are currently listed in columns C (category 1) and A (category 3b) in the AEWA Action Plan, respectively. The international population of the species is censused and monitored every 10 years (Schulz 1999).

Conservation Actions Proposed

The following information refers to the species's European range only: Intensively grazed (>1 cow per hectare) unfertilised grassland was found to attract a higher abundance of this species in Hungary (Baldi et al. 2005), and traditional livestock-farming practices such as creating herb-rich meadows for stock grazing and hay production are thought to be beneficial (Goriup and Schulz 1990). A model used to study the impact of different land use patterns on the species found that sequential (asynchronous) mowing of grasslands may increase the food supply for nestlings, thereby increasing reproductive success (as sequential mowing generates a small number of high-quality foraging patches throughout the breeding season) (Johst et al. 2001). Habitat management for the species should include the periodic flooding of meadows, the creation of a mosaic of native grasslands and meadows, and the retention or creation of ditches, ponds and lakes (Goriup and Schulz 1990). The report also advises management strategies in relation to electricity pylons (e.g. burying or marking aerial cables and preventing disturbance to nests during maintenance) to reduce the threats of electrocution and collision (Goriup and Schulz 1990). Due to the species's habit of defecating on its legs to regulate its body temperature in hot climates it is inadvisable to fit individuals with leg-rings for tracking purposes (dry uric acid builds-up on the legs and hardens around leg-rings, tightening them and leading to injuries) (Goriup and Schulz 1990). Other methods of monitoring movements such as satellite telemetry or patagial wing-tags are therefore advised (Goriup and Schulz 1990).

Login

Login