Saddle-billed Stork (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis)

CAR summary data

Habitat and noted behaviour

Sightings per Kilometre

Please note: The below charts indicate the sightings of individuals along routes where the species has occured, and NOT across all routes surveyed through the CAR project.

Regional Status

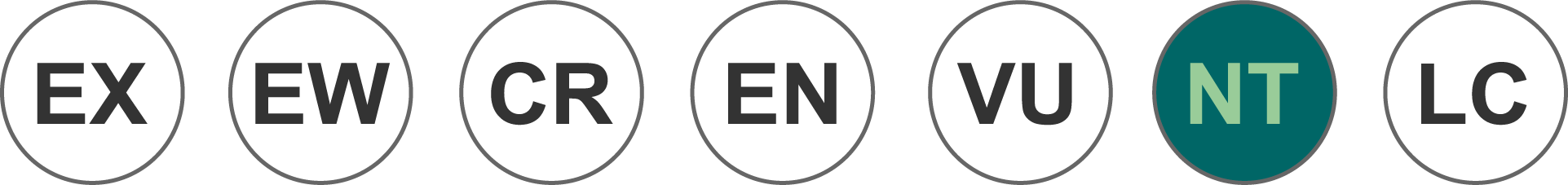

Global Status

IUCN Data (Global)

IUCN 2024. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2024-1 (www)Assessment year: 2025

Assessment Citation

BirdLife International 2025. Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2025: e.T22697706A224821959. Accessed on 18 January 2026.Geographic range:

The species occurs patchily in west Africa across the southern edge of the Sahel, seemingly now largely restricted to protected areas, while from Ethiopia and Sudan and South Sudan south to northern Botswana, south Mozambique and eastern South Africa it is more frequent (Gula et al. 2021). It occurs in Senegal (Saloum River Delta), The Gambia (though may not breed), Guinea-Bissau (Bijagós Islands, one nest recorded [J. Gula in litt. 2024) patchily in Cote d’Ivoire (Comoe National Park), Ghana (Mole National Park), Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger (a connected breeding population in Arli and W National Parks across the three countries), north Cameroon (Benoue, Bouba Ndjida and Waza National Parks) and southern Chad (Zakouma National Park) (Gula 2021). Recent records from Gabon are few and appear to relate to wandering individuals (Gula 2021). In Nigeria the only regular area of occurrence was Yankari National Park, but no more than three individuals have ever been recorded and none have been seen since 2015 (Gula 2021); it may be extinct if it has even been a regular breeding species in recent decades. It is now considered extinct as a breeding bird in both Togo (Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett 2019, Gula 2021) and Mali (Gula 2021).It is common in the rift valley in Ethiopia, and although there is little information was previously common in suitable habitat in Sudan and was, at least previously, abundant in The Sudd in South Sudan (Gula 2021). It is a regularly encountered species in small numbers in wetlands in Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda (Akagera National Park), Burundi (although there is limited habitat), Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and in northern Botswana, southern Mozambique and eastern South Africa. It appears to be only an erratic visitor to Eswatini due to the lack of suitable habitat (Gula 2021). West to Angola the species is regular and may be frequent: recent information is limited but it still occurs north at least as far as Quiçama National Park near Luanda (eBird 2023). In Namibia there are scattered records from the centre but most are in the northeast: nationally there is little suitable habitat and apparently no recent breeding records (Gula 2021). The lack of access for ornithologists to much of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Republic of Congo in recent decades mean that the few records are difficult to interpret, but historically the species was reported to be common in at least some regions (Gula 2021, Gula et al. 2022a).

A thorough investigation of records has been used to model the likely occupancy across the range at 3,071,098 km2 (Gula et al. 2022a). While this value does not constitute an area of occupancy (AOO) as it was not scaled to a 2 km x 2 km grid, it does indicate that the true AOO greatly exceeds thresholds for listing as threatened. However, the recorded extinction as a breeding species from Togo, Mali and possibly Nigeria, plus inferred contraction of the range from peripheral areas (Eritrea, potentially Somalia) and apparent reduction in abundance in DR Congo and Republic of Congo allow the inference of a continuing decline in the AOO, although not the EOO (extent of occurrence).

Habitats:

Habitat It inhabits extensive fresh, brackish or alkaline wetlands (Brown et al. 1982, del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hockey et al. 2005) in open, semi-arid areas (Hancock et al. 1992) and savanna (Hockey et al. 2005), with relatively high abundances of fish (Brown et al. 1982) and with large trees nearby for nesting and roosting (Hancock et al. 1992) (although it avoids deeply forested areas (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hancock et al. 1992)). Suitable habitats include shallow freshwater marshes (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hancock et al. 1992), wet grasslands (del Hoyo et al. 1992), the margins of large or small rivers (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hancock et al. 1992), lake shores (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hancock et al. 1992, Hockey et al. 2005), pans (Hockey et al. 2005) and flood-plains (Hancock et al. 1992, Hockey et al. 2005). Across the range, Gula et al. (2019) found that suitable habitat area may have increased, indicating that factors other than habitat extent are causing the reduction in occupied area. There is uncertainty in the connection of available wetland habitat to population trends, but there does not appear to be a continuing decline in habitat quality.Behaviour There is no evidence that this species undertakes any regular long-distance migration (Hancock et al. 1992), although it is not altogether sedentary (del Hoyo et al. 1992) as some populations make local nomadic movements to optimum foraging habitats (del Hoyo et al. 1992) during periods of drought or when large rivers are in flood (Hancock et al. 1992). Juveniles can move across larger areas (Gula et al. 2022b). Breeding starts late in the rains or in the dry season (del Hoyo et al. 1992), timed so that the young fledge at the height of the dry season when prey is concentrated and easier to obtain (Hancock et al. 1992). The species nests in solitary pairs and usually remains solitary when not breeding (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hancock et al. 1992), although groups of dozens of individuals are not unheard of (Gula et al. 2022c).

Diet Its diet consists predominantly of fish 15-30 cm long (Hancock et al. 1992) up to 500 g in weight, as well as crabs, shrimps, frogs, reptiles, small mammals, young birds, molluscs and insects (del Hoyo et al. 1992) (e.g. large water beetles, termite alates (Hockey et al. 2005)).

Breeding site The nest is a large flat platform of sticks (del Hoyo et al. 1992) placed up to 20-30 m (Hancock et al. 1992) in a tree near water isolated from other trees and sources of disturbance (del Hoyo et al. 1992). It may also nest on cliffs (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Hancock et al. 1992) and in the abandoned nests of other bird species (Hancock et al. 1992).

Population:

There is no direct overall population estimate due to the lack of monitoring in most of the range, uncertainty over movements and connectivity of different areas and the absence of information on the continued occurrence in some parts of the large range. Previously an expert-based estimate of the population was set at between 1,000-25,000 individuals. It is plausible that the true population size falls below the upper bound, however collated count data indicate the minimum number is too low. An initial rangewide assessment of suspected values results in a summed total of regional values of 7,800-19,400 individuals (see below). But with no data for central Africa and noting the low levels of survey coverage (or no coverage) in many areas, the range is increased to 7,800-22,500 individuals. There is further uncertainty in the proportion of mature individuals this represents. Investigating the identification of age-classes Gula et al. (2021) noted dramatic variation in the proportion of adults versus immature individuals between drought and non-drought years. Many of the counts reported below are from aerial surveys, expected to be biased towards detecting the largely white adults. On a precautionary basis a standard assumption that around two-thirds of the reported individuals are mature is applied here. The sum of these regional values suggests a tentative range of 5,200-15,000 mature individuals. Due to the level of uncertainty, this is considered a provisional, suspected value: the assumptions made are intended to be precautionary.The west African population appears to be highly disjunct and is now likely small. Based on the following summary a plausible range falls between 400-1,000 individuals, potentially 250-700 mature individuals. The connected habitat across Benin, Burkina Faso, and extreme SW Niger seems likely to hold only low hundreds at most, with 102 individuals in Pendjari National Park, Benin, in 2008 the largest reported count (Gula 2021). Regular flood season counts in Waza-Logone, Cameroon, between 1992-2000 peaked at 77 in 1999 (Scholte 2006), while additional individuals are present in Benoue NP, Bouba Ndjida NP and Faro NP (eBird 2023). The total for the country is unlikely to exceed a few hundred birds. Similar or smaller numbers are likely to remain in Chad, centred on Zakouma National Park and surrounding wetland habitat. Ghana now only has a tiny number in Mole National Park. Very small numbers continue to be observed in Senegal but appear to be wandering individuals, this may also be true in Gabon (eBird 2023). In Guinea-Bissau the species only regularly occurs in the Bijagos Archipelago, where there are estimated to be only 9 individuals (Dodman and Sá 2005). In Mali a small number are reported to occur to the east of the Inner Niger Delta at Lake Korarou (Gula 2021), but hydrological changes to the main Inner Niger Delta are thought to have caused the loss of the species (Zwarts et al. 2009) and current numbers must be tiny. There are no recent records from the Gambia, very few persist in Côte d'Ivoire and it is thought to have ceased breeding in Nigeria.

For east Africa, including Sudan and South Sudan, the total population appears to be much larger than that in west Africa. Summarising counts and records across suitable habitat for this region suggests a minimum of 6,000 individuals and maximum of 16,000 individuals, suspected to represent between 4,000 and 10,700 mature individuals. In South Sudan, between 3,640 and 4,158 individuals were counted during aerial surveys of the Sudd in 1979–1981 (Mefit-Babtie Srl. 1983, Howell et al. 1988, as reported in Gula et al. 2019). The area of the Sudd designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance is 57,000 km2, though the extent varies greatly between dry and wet seasons and depending on annual water flow. The ratio of different wetland land cover classes assessed in March has remained relatively constant throughout the Sudd between 2000 and 2020, despite considerable variation at smaller scales, at 80-84% seasonally-flooded grassland, 14-19% marsh and <2.5% open water (Ruuskanen 2021), however the mean area of open water declined by 19% (SE 5%) between 1984 and 2015 (Gula et al. 2019). In the absence of repeat surveys this population is assumed to remain large, but the age of the data introduces significant uncertainty in the global population size and reduction in area available in the Sudd suggests a decline may be suspected. A provisional current value of 2,000-5,000 individuals is used for South Sudan, likely representing between 1,300-3,300 mature individuals.

Aerial surveys in Tanzania in 1993 produced an estimate of 1,398 individuals across 4,188 km2 of the Moyowosi-Kigosi Game Reserve complex, leading to an extrapolation of around 6,000 individuals in Tanzania as a whole (Baker 1997, Gula 2021). Again the age of this data adds uncertainty to the estimate but the species remains frequently recorded without reports of range contraction or significant declines, hence a precautionary current value of between 3,000-6.000 individuals is given a a plausible range for Tanzania, or 2,000-4,000 mature individuals. There do not appear to be any population estimates available for Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda or Burundi though the species is present in suitable habitat throughout. The total number of birds present is likely to exceed a minimum of 1,000 individuals but to fall below 5,000 individuals, or between 650 and 3,300 mature individuals.Very little information is available on the status of the species in Somalia, where it may only be a non-breeding visitor (Gula et al. 2019, Gula 2021).

Little recent information is available for central Africa. Birds are present in Central African Republic and DR Congo. While there is no indication of numbers, generally the current population is not expected to be large, although it was historically reported as common in Katanga province and the Kasai River in DR Congo (Chapin 1932). No value is given, but it is likely that birds remain present, and indeed a sizable number may still occur in this vast area.

For the remaining southern part of the range the regional population appears to most likely fall between only 1,400- 2,300 individuals, or 900-1,600 mature individuals.

Direct counts have also been made in several protected areas in Zambia. The Liuwa Plain appears to be the most significant site. It was estimated to hold 198-235 individuals in November 2001, from a count of 66 birds, and 314 individuals in July 2003, from 157 observed: both surveys indicated between 100-120 pairs were present (Beilfuss et al. 2004). Recent photographic mark-recapture methods found a minimum of 117 unique individuals within 330 km2 of which 32 were adults but some additional birds were present (Gula et al. 2021, 2022b) while in 2019 when drought affected the area only 14 unique adults were located (Gula et al. 2021). The flats cover an area of approximately 6,500 km2 (Kamweneshe and Beilfuss 2002a), however it is unlikely that the sampled area is representative of the whole as surveys were targeted. Bangwelu Swamp is another important site and an aerial survey estimated 275 birds in October 1983 (Howard and Aspinwall 1984, Gula 2021), but only 18 (including 5 pairs) were observed in a 12 hour survey flight in July 2002 giving an estimate of fewer than 40 individuals present (Kamweneshe et al. 2003, Gula 2021). It is uncertain whether this apparent decline is due to genuine declines or bird movements or methodological issues with single transect aerial surveys. Fewer than 20 individuals were estimated to occur in both Kafue Flats in 2001 (Kamweneshe and Beilfuss 2002a) and Busanga Swamp in Northwestern Province in 2003 (Beilfuss et al. 2004) and fewer than ten individuals were estimated to be present in 2001 in the large Lukanga Swamp (210,000 ha) (Kamweneshe and Beilfuss 2002b). None were reported in a 2015 repeat survey of Kafue Flats (Shanungu et al. 2015). Unknown numbers occur in the Luangwa Valley and elsewhere in the northeast of the country (J. Gula in litt. 2024); likely to represent a similar number of breeding pairs as in Bangwelu, 10-20 pairs but potentially more. Overall, numbers in Zambia appear relatively small, considering the surveys documented above cover much of the large areas of suitable wetland habitat in the country. There appears to be much movement between sites according to water conditions, but a range of 130-180 pairs (100-120 in the Liuwa Plain, 10-20 in Bangwelu Swamp and Luangwa Valley, and 10-20 for the rest of the country) suggests the number of mature individuals in Zambia is between 260-360 mature individuals.

A small population is present in Malawi, with birds resident in Liwonde NP but total numbers for the country are suspected at below 50 individuals.

In Mozambique, aerial surveys of the Marromeu complex in the Zambezi Delta recorded 36, 7 and 31 individuals in 1995, 1996 and 1997 (Beilfuss and Allan 1996, Bento and Beilfuss 2000), while 68 were counted in the delta in 1999. This suggests local movements of birds around the delta and from outside. Surveys in Gorongosa National Park counted 43 individuals in 2014 and 2016 (M. Stalmans, unpublished data). While coverage is clearly deficient, there are unlikely to be more than 100 pairs/200 mature individuals present, although notable areas of suitable and unsurveyed habitat are present, especially in north Mozambique.

The Okavango Delta in Botswana has the most complete aerial census data series of the major sites for the species; 1,069 (CI: 879–1,259) individuals in 2001, 812 (669–956) in 2002, between 1,045–1,778 in 2003; 1,040 (801–1,278) in 2010 and 960 (775–1,145) in 2014 (Gula 2021), but then a statistically significant drop to 552 (429-676) in 2018 (Chase et al. 2018). Given the species is known to disperse according to water availability, further data is required to assess whether this is a redistribution of birds or a genuine rapid reduction in the delta. A provisional value of 500-1,050 individuals and approximately 330-700 mature individuals is here assigned to the Okavango.

Populations in Zimbabwe are found in Hwange NP, Matusadona NP and along the Zambezi River but also in the Savé River in the southeast. In the absence of clear data this population is nominally suspected to fall between 100-200 individuals and 70-130 mature individuals.

The South Africa population is estimated at 120-150 individuals (Botha 2015), most within Kruger National Park. Here a mark-recapture approach using photographs from visitors allowed the discrimination of 40 adult individuals, but this was a bare minimum as many photographs had to be discarded (van den Hoven and Reilly 2012).

Numbers in Namibia are small and predominately occur within and around Etosha NP, while there is uncertainty over how many are present in Angola but numbers are assumed low, 25-50, on a precautionary basis.

The greatest uncertainty in the population size lies in the numbers using the Sudd wetlands, which on the values compiled holds up to a quarter of the total population.

Threats:

Trapping for trade is potentially the most significant threat given the potentially low global population size (Gula et al. 2022a). Trade in live birds, trophies, skins and eggs occurs at a relatively high level and the species has been recorded in four out of seven global trade databases (Donald et al. 2024). A large proportion of traded birds are wild-caught (Gula 2021) and there is no clear assessment of the current rate of offtake, hence no information to inform the likely sustainability of trade. However, the observed disappearance of the species from large parts of west Africa coincides with recorded high levels of large waterbird trapping for food and for trade, including belief-based use (Nikolaus 2001, Zwarts et al. 2009, Gula and Barlow 2023).The species has been impacted by the loss and degradation of wetland habitats (Gula 2021). Widespread conversion of protected areas to agriculture in Togo since the 1990s appears to have driven the extirpation of the species from the country (Gula 2021) and the conversion and degradation of wetlands due to the expansion of land used for agriculture overall is suspected to have caused population declines and to be a factor in the recorded range contraction noted in west Africa (Gula et al. 2019, Gula 2021). While the overall availability of wetland habitat does not appear to have significantly changed (Gula et al. 2019), the species' need for particular water levels makes it difficult to determine actual habitat trends (Gula 2021, Gula et al. 2022a). Large-scale hydrological projects apparently caused the rapid and near-total abandonment of the Inner Niger Delta in Mali (Zwarts et al. 2009), though it is uncertain whether these individuals relocated hence the population impact is uncertain. Dams on the Senegal, White Volta and Oti Rivers also appear to have caused declines (Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett 2014, Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett 2019, Gula et al. 2019, Gula 2021), while excess water since 2000 coincided with the disappearance of the species from Namibia's Nyae Nyae Conservancy (Gula et al. 2019, Gula 2021).

Conservation measures:

Conservation actions in placeThe species is not currently listed in the CITES Appendices. Previously it was included on Appendix III by Ghana from 1976 to 2007 (UNEP-WCMC 2007, Species+ 2024). Occurs in numerous protected areas across the large range, and efforts to restore and expand wetlands such as in the Waza-Logone Floodplain in Cameroon and Chad have occurred (Scholte 2006). A telemetry study investigated dispersal but was limited by drought leading to a lack of breeding (hence no juveniles to track) and by the difficulty of trapping the species (Gula et al. 2022b). Monitoring is currently very limited, with the species occurring at sites covered by the International Waterbird Census, but coverage of the population is poor due to the low density of the species and its movements in response to water conditions. Aerial surveys for mammals and large birds are the most effective monitoring approach for the species, but have only occurred regularly for the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

Conservation actions needed

Survey to estimate current population size in South Sudan, Ethiopia and Chad. Continue/restart surveys to assess population in the Okavango in Botswana. When feasible, survey areas of DR Congo and Central African Republic with previous records to determine current occurrence and status. Efforts are needed to understand the level of offtake for trade, sources of traded individuals and key markets.

Rationale:

Despite a very large range, the species is sparsely distributed and the overall population size may well be small, although it is uncertain. In west Africa the species has been lost as a breeding bird from a number of countries and there is evidence of significant reduction in abundance in others. These losses are not thought to be offset by any increases elsewhere in the range and the population is inferred to be declining. While the fragmentation of the west African range may have led to a degree of isolation, the species is well capable of long-distance movement and wide dispersal. On a precautionary basis it is considered to occur as a single population. Based on the suspected lower potential bound of the population size, in conjunction with an ongoing decline, Saddle-billed Stork is assessed as Near Threatened.Trend justification:

The population is inferred to be declining, noting the loss of the species as a breeding bird from Nigeria, Togo, Mali, and Senegal, reduction in the number of occupied atlas squares in Kenya and modelling of reporting probabilities from the African Bird Atlas Project (Lee 2024).Apparent extirpation as a breeding species from Togo, Mali and possibly Nigeria suggest that the west African population is declining (Gula et al. 2019, 2022a, Gula 2021), and although there is no recent comprehensive survey it is suspected that the population in the Sudd has reduced from the 3,640-4,158 counted in 1979-1981 (Mefit-Babtie Srl. 1983). A reduction in the occupancy has been recorded in Kenya (Kenya Bird Trends 2024) and the probability of encounter using African Bird Atlas Project data appears to be declining based on a logistic regression model (Lee 2024). Although data are sparse across the very large range and key parts of the range are unsampled, such that the power of this approach is likely to be poor, it certainly indicates that the population is likely to be declining.

Login

Login