Southern Black Korhaan (Afrotis afra)

CAR summary data

Habitat and noted behaviour

Sightings per Kilometre

Please note: The below charts indicate the sightings of individuals along routes where the species has occured, and NOT across all routes surveyed through the CAR project.

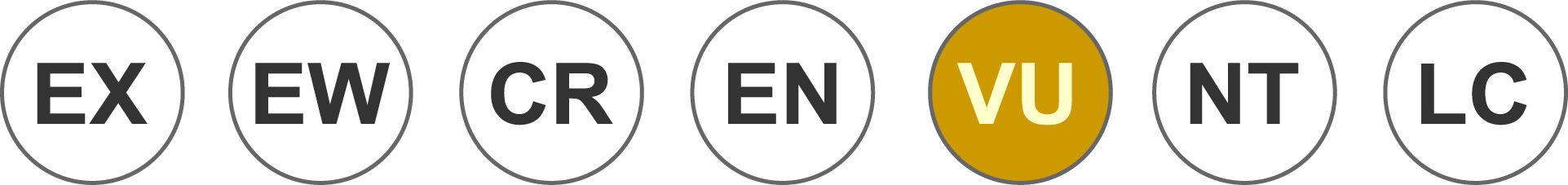

Global Status

IUCN Data (Global)

IUCN 2024. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2024-1 (www)Assessment year: 2025

Assessment Citation

BirdLife International 2025. Afrotis afra. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2025: e.T22691975A231842203. Accessed on 03 March 2026.Taxonomic notes:

Afrotis afra (del Hoyo and Collar 2014) was previously placed in the genus Eupodotis.Afrotis (Eupodotis) afra and E. afraoides (Sibley and Monroe 1990, 1993) are retained as separate species contra Dowsett and Forbes-Watson (1993) who included afraoides as a subspecies of E. afra.

Geographic range:

This species is endemic to southwestern South Africa, where it occurs in Northern Cape, Western Cape and Eastern Cape provinces from Little Namaqualand south to Cape Town and then east to Grahamstown. It was historically very common but appears to have become scarcer and its distribution more fragmented (Hofmeyr 2012).A detailed investigation into the occupancy of different land use/land cover classes determined that the total suitable habitat area in 2020 was 20,355 km2 (Evans 2023): while this value has not been scaled to a 2 x 2 km grid and does not represent an area of occupancy for the species, it does indicate that the occupied area is not currently small.

Habitats:

The species is restricted to the non-grassy, winter rainfall or mixed winter-summer rainfall fynbos and succulent Karoo biomes, and the extreme south of the Nama-Karoo biome, in a narrow strip along the southern and western coastlines of South Africa (Hofmeyr 2012). It also occurs in semi-arid scrub and dunes with succulent vegetation, and extends into renosterveld scrub and semi-arid karoo (del Hoyo et al. 1996, Hockey et al. 2005). It occurs occasionally in cultivated fields with nearby cover (Hockey et al. 2005). Quantifying the species' use of land use/land cover classes, Evans (2023) found that low shrubland in the fynbos, succulent and Nama Karoo biomes as well as other low shrubland were suitable, as was natural grassland, and fallow land and old fields where this had developed into low shrub. The species has a significant preference for the fynbos biome, while annual cropland was found to not be suitable (Evans 2023).The extent of the species' preferred habitat, fynbos shrubland, decreased by around 36% between 1990 and 2020, which was more rapid than the overall c. 20% reduction in all potentially suitable habitat types (Evans 2023). It is therefore estimated that there is a continuing decline in the area, extent and quality of habitat.

The diet consists of insects, small reptiles and plant material, including seeds and green shoots (Hockey et al. 2005) and it is considered sedentary (Kirwan et al. 2023).

Population:

The global population size has not been quantified, but the species has been described as 'uncommon to common' (Hockey et al. 2005). Recorded densities were higher in the succulent Karoo than the Nama Karoo, at maximum values of 1.61 individuals per 100 km (standard error 0.43) and 0.29/100 km (0.15) (Shaw et al. 2016), while at the regional level densities were highest in the Eastern Cape (4.04/100 km in summer and 2.53/100 km in winter) and lower in Overberg (0.52/100 km in summer, 1.19/100 km in winter) and Swartland (0.63/100 km in summer and 1.74/100 km in winter) (Hofmeyr 2012). However the former study recorded sharp reductions in the density of the species between the 1980s and 2010s, such that overall recent densities were less than half those given above (Shaw et al. 2016).Threats:

Conversion of natural vegetation to agriculture appears to be the primary threat as the driver of habitat loss (Evans 2023). Most habitat loss has been due to an increase in the area used for commercial annual crops (Evans 2023), with the intensity of the agriculture practice also noted to have increased in recent years (D. Young in litt. 2013). Coordinated Avifaunal Roadcounts project data show that, whilst the species can use farmland where little else is available (especially in the Overberg, where c. 80% of land is transformed), in general they prefer natural veld (Hofmeyr 2012). Patches of indigenous vegetation have decreased in size and become more isolated (Evans 2023). Increasing agricultural activity is likely to not only cause a decrease in suitable breeding territories, but also decreased breeding success as a result of increased disturbance related to farming activities and increased chick and egg predation because of a general decrease in cover and an increase in predators such as Pied Crows (Hofmeyr 2012). It is also possible that adults have suffered increased predation rates and even increased starvation because of the decline in cover and suitable habitat (Hofmeyr 2012).In common with other bustards the species is at risk from collisions with powerlines (Silva et al. 2023) and wind turbines (Perold et al. 2020, BirdLife South Africa 2025). Five individuals were recorded killed by one wind farm in a study summarising mortality from 20 facilities (Perold et al. 2020), while four fatal collisions with powerlines have been observed (Shaw et al. 2010, 2018, Silva et al. 2023). The power to detect mortality events at wind energy facilities is low, though it may be the case that it impacts on this species depend on the location and siting of particular facilities. The rapid increase in the number of new wind energy facilities suggests that this threat is likely to grow. But there are already many thousands of kilometres of unmonitored powerlines, such that rates of mortality are likely to be significant and may be a major driver of population reductions noted where habitat appears to remain suitable.

Climate change impacts are being widely recorded in natural habitats within the range of the species and may aggravate the threat of habitat loss (Hofmeyr 2012). The Western Cape is predicted to become drier in the next decades, which may thin out the dense vegetation the species requires for nesting and result in higher female mortality and lower reproductive success (Evans 2023). Species richness and abundance of species of fynbos and grasslands have been predicted to decline significantly due to climate impacts over the next few decades (Huntley and Barnard 2012, Lee and Barnard 2016), it is inferred that impacts would negatively affect the present species but further study is needed.

Conservation measures:

Conservation and research actions underwayCITES Appendix II. The Gouritz Cluster Biosphere Reserve’s Corridors and Rehabilitation Programme is undertaking habitat restoration in conjunction with private landowners in part of the range (Evans 2023). Approximately 47% of suitable habitat is found within protected areas (Evans 2023). The species is monitored through the SABAP protocol and partially through the Coordinated Avifaunal Roadcount (CAR).

Conservation and research actions needed

A direct assessment of the total population size is required using density estimates stratified by biome, and assessing breeding success in the centre and edges of range would allow the determination of source and sink populations (Evans 2023). These data would permit the assessment of the current network of protected areas for the species' viability. Research is also required into the species response to fire regime and to predicted and observed climate change impacts. Undertake an assessment of collision rates with powerlines and identify problematic sections for mitigation (M. Pretorius in litt. 2025).

Login

Login