Southern Ground Hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri)

CAR summary data

Habitat and noted behaviour

Sightings per Kilometre

Please note: The below charts indicate the sightings of individuals along routes where the species has occured, and NOT across all routes surveyed through the CAR project.

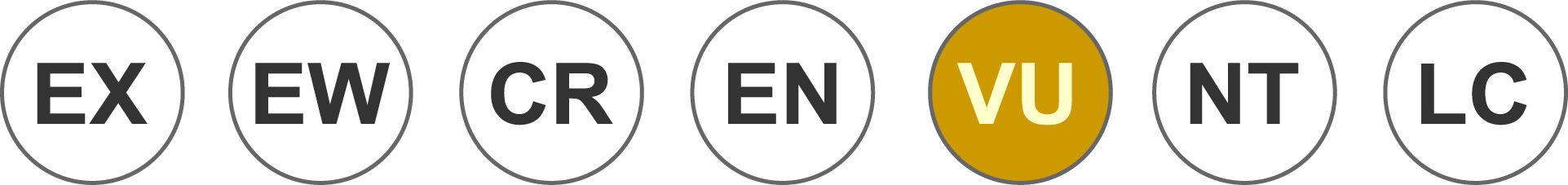

Regional Status

IUCN Data (Global)

IUCN 2024. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2024-1 (www)Assessment year: 2025

Assessment Citation

BirdLife International 2025. Bucorvus leadbeateri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2025: e.T22682638A266675349. Accessed on 22 January 2026.Geographic range:

This species is found from southern Kenya, Rwanda, and Burundi, through south-eastern Democratic Republic of Congo and Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe; south-west to Angola and northern Namibia; and south through Botswana and eastern South Africa, including Eswatini and Lesotho (del Hoyo et al. 2001, Stevenson and Fanshaw 2002).Habitats:

It lives in groups of 2-9 members, rarely 12, and is a co-operative breeder, with the dominant pair assisted by adult, mostly male, and immature helpers to defend a territory and provision a nest (L. Kemp in litt. 2016). The breeding pairs have previously been assumed to be monogamous, but molecular techniques have revealed that extra-pair copulations do occur (Theron et al. 2013). Groups occupy year-round home ranges of 50-100km2, determined primarily by the availability of suitable nest sites and food availability during the dry season (Kemp 2005, Wilson and Hockey 2013). Laying occurs in large cavities in trees, cliffs or earth banks (L. Kemp in litt. 2016), mainly from September to December, with a clutch of 1-3 (usually 2) eggs, although only one survives to fledging (del Hoyo et al. 2001, Chiweshe, L. Kemp in litt. 2008). One study in South Africa showed that a family group produced on average only one fledgling every nine years, although birds in the Okavango Delta appear to breed more frequently (del Hoyo et al. 2001, S. Tyler in litt. 2010). Juvenile mortality is reported to be high in a large protected area, and this is likely to be even higher in unprotected areas where anthropogenic threats are present (Kemp 1990).It inhabits woodland and savanna, also frequenting grassland adjoining patches of forest up to 3,000 m in parts of its range in eastern Africa (del Hoyo et al. 2001). In Zimbabwe, Southern Ground-hornbills are most frequently recorded in Mopane (Colophospermum mopane) woodland, which appears to be a key habitat for both foraging and breeding (Chiweshe 2007). They also utilise a range of other habitats, including Acacia savanna, grasslands, agricultural land, floodplains, riverine woodland, mixed savanna and miombo woodland. The species shows a strong association with Baobabs (Adansonia digitata) and other substantial riverine trees. Notably, Mopane woodland also supports the highest density of Baobabs in Zimbabwe, as the two species share similar climatic requirements. Habitat suitability is further influenced by rainfall and soil type, with the species occurring more frequently in drier Sweetveld areas than in Sourveld. However, suitability may also be reduced by anthropogenic pressures such as overgrazing and inappropriate fire regimes, which can degrade habitat quality and reduce prey availability even within otherwise preferred vegetation types (Chiweshe 2007). The species fares well in protected areas where human threats are excluded and rural areas where cattle assist in maintaining their preferred short grass habitat.

Its diet is mainly made up of arthropods, and, especially during the wet season, snails, frogs and toads, and sometimes larger prey such as snakes, lizards, rats, hares, squirrels or tortoises. It will on occasion feed on carrion, taking scraps and associated insects. Fruits and seeds are also recorded in its diet, although infrequently (del Hoyo et al. 2001).

Population:

The global population size has not been quantified, but the species is reported to be widespread and common but sparse (del Hoyo et al. 2001). The species has large spatial needs which results in low densities and small population size per unit area (Kemp 1995). The population in South Africa in 1992 has been estimated at c.1,400 mature individuals - perhaps a 50% decline on historical population numbers (L. Kemp in litt. 2008), although certain areas are seeing recoveries due to groups recolonising areas (e.g. Limpopo Valley; Theron et al. 2013). In Botswana it is still frequent in the Okavango Delta and Chobe areas, where it occurs at higher densities than it averages in South Africa (S. Tyler in litt. 2012). Zambia is thought to represent a stronghold for the species, with relatively high group densities and indications of strong reproductive output within the surveyed population (Gula and Phiri 2020).Threats:

The primary threat to the species is lead poisoning. During hunting activities, lead bullets fragment within carcasses, contaminating both tissue and discarded offal. As scavengers, Southern Ground-hornbills consume this offal and ingest the lead fragments (Mabula Ground Hornbill Project 2025). They are highly sensitive to lead toxicity, with adverse effects observed at blood concentrations as low as 10 μg/dl, far lower than in vultures, where effects typically occur above 45 μg/dl. It is hypothesised that their particularly acidic digestive tract may enhance lead absorption. The species is vulnerable to secondary poisoning through the ingestion of pesticides and rodenticides (Mabula Ground Hornbill Project 2025). Entire groups may die after scavenging carcasses deliberately poisoned to target carnivores. Additionally, control programmes aimed at reducing Red-billed Quelea (Quelea quelea) populations have been implicated in widespread declines, as the hornbills may consume poisoned Quelea carcasses, despite not being the intended target (Mabula Ground Hornbill Project 2025).In Zimbabwe, key threats outside protected areas include competition for space with an expanding human population, particularly on the Mashonaland Plateau, and the loss of large, hollow nesting trees due to harvesting for firewood, agriculture, and dugout canoe construction (Chiweshe 2007, Msimanga 2004). Baobab trees are further impacted by fibre extraction for crafts and construction materials, as well as damage caused by elephants during drought periods (Herremans 1995). Widespread livestock grazing has also lead to the erosion of suitable grassland in Kenya, with perhaps only 10% of suitable habitat remaining in the country (S. Thomsett in litt. 2010).

Cultural beliefs and practices pose a threat to the species. In some regions, particularly South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Malawi, the bird is seen as a harbinger of death, destruction, or deprivation (Coetzee et al. 2014). While some cultures avoid or protect the bird due to its association with death, others chase, stone, or kill it, believing its presence signals impending calamity. The species is also viewed as a protector against evil spirits, lightning, and drought, leading to its use in rituals intended to ward off these threats, particularly in South Africa (Coetzee et al. 2014). In Malawi and Zambia, the cultural impact appears neutral. Additionally, in Zimbabwe and Malawi, the species is believed to possess the power to alter perceptions and expand consciousness, often used to create illusions or remote viewing experiences. Rituals involve ingesting the bird’s ashes or using its parts to enhance mental abilities. In South Africa, the bird is used by local leaders to assert authority, with rituals that involve bathing with the bird’s head to gain a commanding presence (Coetzee et al. 2014). These beliefs are largely destructive for the species, as they result in the capture and killing of the species for ritualistic purposes. Persecution may also occur due to the species' territorial nature, which leads individuals to attack their reflection in window panes, resulting in property damage and conflict with local residents (Theron 2011). This species is mainly traded locally for rituals and medicine, as well as the large scale aviculture trade (Coetzee et al. 2014, Kemp and Neller 2015).

There has also been a recurrence of the species landing on transformer boxes and getting electrocuted (Mabula Ground Hornbill Project 2025). This species can be susceptible to Newcastle's Disease Virus (L. Kemp in litt. 2016), and may be under threat from stepping on land mines in areas of conflict (L. Kemp in litt. 2016). It can become heat stressed and exhibits heat avoidance behaviour in temperatures above 26oC, and increasing temperatures with climate change could pose a threat (L. Kemp in litt. 2016).

Conservation measures:

Conservation Actions UnderwayIt is still protected by tribal lore in many areas, and occurs in several reserves and at least seven national parks (del Hoyo et al. 2001). The Mabula Ground-Hornbill Project (MGHP) (2025) is dedicated to halting and ultimately reversing the decline of the Southern Ground-hornbill in southern Africa through a multifaceted conservation strategy. A key component of their work is long-term monitoring, conducted on a four-year cycle using a grid-based system to track population trends and inform conservation planning. The MGHP is actively restoring populations through innovative reintroduction methods, beginning with the hand-rearing of second-hatched chicks that would have otherwise perished, followed by structured releases into suitable habitats once they are fully fledged. The project also implements threat mitigation strategies, such as covering windows to prevent glass breakage and human-wildlife conflict, and developing deterrents to prevent birds from perching on transformers, thereby reducing the risk of electrocution. The MGHP is also addressing the critical shortage of natural nesting sites, primarily caused by the loss of large cavity-bearing trees such as Baobabs and Marulas, by designing and deploying artificial nests. These specially engineered nests replicate the structure of natural cavities and are made from durable, weather-resistant materials. Key design features include ventilation holes, drainage, reinforced perches, and water-resistant entryways, ensuring suitability and longevity. The artificial nests are installed within territories of wild groups that lack suitable nesting sites, thereby supporting breeding and improving group stability. Education is another cornerstone of their work, with outreach efforts targeting rural residents and school learners to raise awareness of the threats facing the species and promote coexistence. In addition, MGHP supports and conducts research to improve conservation outcomes. Current projects include testing satellite tracking devices on ex-situ birds, assessing the effectiveness of aversion training to prevent released individuals from landing on hazardous infrastructure, and analysing lead levels in individuals showing signs of toxicosis. In the Matobo District of Zimbabwe research is being conducted into emerging threats from small scale farming (L. Kemp in litt. 2016). Conservation Actions Proposed

Long-term studies are needed to understand how the species adapts to seasonal changes in the highly variable Limpopo environment (Theron 2011). This includes monitoring the seasonal abundance of invertebrate prey using methods like pitfall traps and sweep netting, and correlating food availability and climatic conditions with breeding outcomes. Radio-tracking of more groups in the region will help refine knowledge of territory sizes and movement patterns (Theron 2011). Furthermore, comparative studies across the species’ broader range, especially in regions with smaller territories, are recommended to better understand habitat requirements and to support conservation planning at a landscape scale. Integrating these ecological insights with targeted management actions will enhance efforts to stabilise and expand populations across southern Africa (Theron 2011). Further identify the degree of impact the harvesting of this species may have. Conduct population surveys and establish monitoring to assess population trends. Identify key strongholds of the species and prevent further habitat degradation in these areas. Collect sighting data at a national scale to build up a database for comparison to existing atlas data and for range states engaged in the Southern African Bird Atlas Project to ensure maximum coverage. Monitor trade of this species. Continue awareness campaigns to prevent persecution, and accidental mortalities due to abusive and non-targeted use of pesticides and poisons. Promote and revive existing cultural protection. Continue to research the effectiveness of artificial nest-sites. Protected area (PA) networks in Zimbabwe play a critical role in the conservation of the Southern Ground-hornbill, with areas with higher protection status associated with greater habitat suitability for the species. Research by Mudereri et al. (2021) projects that 8% of suitable habitat currently within PAs may become unsuitable by 2050 due to environmental changes. However, a projected decline in suitability is expected in eastern PAs, while western PAs may become increasingly suitable. Conservation planning should therefore account for potential range contractions in the east and incorporate strategies to support a westward habitat shift.

Rationale:

Secondary poisoning, trade and persecution are estimated to have caused significant population declines in South Africa and there are anecdotal reports that they have caused declines in other range countries. There is a high probability that such threats and subsequent declines will continue into the future, and as such this qualifies as Vulnerable. In addition, the species' life history strategy (long-lived, slow-breeding) puts the species under greater possible threat of declines. More accurate trend data may become available in the near future and so further reassessment may be required in the future.Trend justification:

An assessment of the species' status in South Africa (L. Kemp in litt. 2008) estimated a 20% loss in the area of suitable habitat within the species' national range in the previous 15 years. If this figure is used to project declines into the future, this equates to a population decline of 69% over 79 years (three generations). Additionally to habitat loss, other significant threats contributing to population declines are ingestion of lead, poison, human-wildlife conflict, electrocution and being hunted for ritualistic purposes (Theron 2011, Coetzee et al. 2014, Mabula Ground Hornbill Project 2025).Declines have continued and assessments in Namibia as well as South Africa, Lesotho and Eswatini, have listed the species as Endangered (Simmons 2015, Taylor and Kemp 2015). Although data for other range countries are lacking, several threats are also thought to be causing population declines in Kenya (S. Thomsett in litt. 2010), Botswana (S. Tyler in litt. 2010) and Zambia (R. Tether, P. Leonard and L. Roxburgh in litt. 2010), though rates of decline in Zambia, which is likely the stronghold, are thought to be slower than elsewhere (P. Leonard and L. Roxburgh in litt. 2010, Gula and Phiri 2020).

Due to limited data across much of its range and the difficulty of accurately quantifying trends for a long-lived species, a slightly broad decline of 30–49% over 79 years (three generations) is suspected. This range reflects the severity and breadth of threats in many areas, balanced against slower declines in regions such as Zambia.

Login

Login